What does a bumblebee have on its hind legs. Determination of bumblebees of the Leningrad region by color (off-topic)

When I was at school, I studied entomology in the circle of AV Kupriyanov at the university. In particular, the issue of bumblebees - I made a list of those species that we have, and also came up with ways to identify them easier. Unfortunately, the possibilities of the schoolgirl were extremely limited - I was engaged in catching and counting bumblebees only where and when they brought me, there was no Internet, there was also no camera, of course, and study took away almost all the time. But there was an opportunity to use a binocular, an academic determinant, free access to the ZIN library and perseverance :) Due to the excess of free time, now I want to remember the past and put in order what was written in childhood. At the same time, let it lie here, suddenly it will come in handy for someone - even if this is not a scientific work, but definitely not bullshit.

By the way, most of the bumblebees were released into the wild after an external study, and only a part in the name of science was euthanized with chloroform and dried - I don’t think that this had any effect on the general population :)

The female bumblebee is different from the male the fact that, firstly, it has a sting, and secondly, its hind legs form “baskets” for collecting pollen (it looks like a shiny dent surrounded by long bristles - or like pollen balls on the legs when the pollen is already collected). Counting the segments of the antennae and the number of segments in the abdomen is already for specialists. In addition, in many species of bumblebees, females and males differ in color.

In cuckoo bumblebees, "baskets" on the paws are absent in both sexes, since they do not collect pollen for their offspring. But the female has a sting.

Bumblebee Species Definitions

The main features for identifying species:

- color - it is diverse, but not so much that all species can be distinguished by it, moreover, it varies

- the structure of the head - the length of the jaws, the location of the eyes, etc.

- males can be clearly identified by the structure of their tick-like genitalia - if the main organ has a certain function and therefore is similar for everyone, then the "pincers" surrounding it are very diverse and unique for each species.

But in order to see anything other than color, the poor bumblebee must be caught, dried and examined under magnification, and for details, besides, boiled in alkali and dissected. And since there are not so many species of bumblebees in a limited region, one color is quite enough to identify "by name" most of the bumblebees encountered. Just by eye, while the bumblebee is doing its business on the flower :)

So a list of bumblebees with a description of their color (and without buzzwords) is a useful thing. The region to which my list refers can be conditionally called the "north-west of the Russian Federation", but in reality this refers primarily to the Leningrad region. According to the maximum estimates, about 20 species of bumblebees live here, I caught 14.

I determined bumblebees according to the academic publication "Key to Insects of the European Part of the USSR" ed. Medvedev (section on bumblebees - edited by Panfilov) as accurately as possible. It is not very clear and logical. If something in the ideas about the classification of bumblebees has changed since then - sorry, I don’t know. For some of the renamed species, I found new names on the Internet and indicated here.

Color patterns

The hair colors of our bumblebees are primarily black, yellow, red and white, less often gray, distributed in stripes. In female workers of most species, the coloration is distributed in clear, well-defined bands. Males are generally lighter in coloration, often with additional yellow stripes, and black hairs may be diluted in varying proportions with lighter ones, making the coloration bands less distinct. Intraspecific variability occurs in the same direction. But at the same time, the main color scheme remains constant within the species in both sexes. If you take a closer look at least a little, it will not be difficult to identify such "schemes" by eye.

Conventions

The coloring of bumblebees of each species is presented by me in the form of conditional schemes. Drawn, I'm sorry, in a simple way. Different fill intensity is a side effect of working in paint, the thickness of the stripes is approximate. White color is indicated on the diagrams as a small-shaded area with a speck.

The main body parts of bumblebees (as well as other insects) are the head, chest and abdomen. In my diagrams, they are presented in the form of three circles.

The upper circle of this scheme denotes the head, and the black or colored spot in it denotes the color of the tuft of hairs on the bumblebee's forehead. On some schemes, the color of these hairs is not indicated.

the middle circle indicates the chest and the color of the hairs on it

the lower circle indicates the abdomen and the color of the hairs on it

COMMON SPECIES

The species of bumblebees listed in this section can be found in almost any meadow, and in most cases the bumblebee encountered will be one of the species from this short list.

Bombus lapidarius (rock bumblebee, red-tailed bumble-bee) (Wikipedia)

Bumblebee rich black color with a bright red belly.

Bombus lucorum (burrowing bumblebee) (Wikipedia)

The most common of our bumblebees with yellow stripes on the carcass and a white tip of the abdomen (this color option is not very original).

By coloring, it is little different from the earthen bumblebee (Bombus terrestris), but the earthen bumblebee is distributed further south than the Leningrad region.

Bombus agrorum, now B. pascuorum (field bumblebee) (Wikipedia)

Fairly light bumblebee with a whole rufous breast and a black belly with a rufous tip.

Bombus pratorum (meadow bumblebee) (Wikipedia)

A bumblebee with a distinct yellow stripe on the chest and a rufous tip of the abdomen.

| female forehead hairs black belly black with rufous tip |

|||||

| male forehead hairs yellow chest yellow in front, black in back the abdomen is black with a red tip, yellow at the base OTHER TYPES

Bombus equestris, now called B. veteranus (horse bumblebee) Fairly light bumblebee with numerous indistinct gray stripes. Bombus derhamellus, in a new way B. ruderarius (small stone bumblebee, red-shanked bumble-bee) (Wikipedia) Bombus hypnorum (urban bumblebee, tree or new garden bumble-bee) (Wikipedia)

Bombus schrencki (Schrenk bumblebee)

Bombus hortorum or Bombus ruderatus

Psithyrus campestris (field cuckoo bumblebee) PS: Photos of bumblebees are taken from the Internet, if possible from Wikipedia. Clicking opens the page where the photo was stolen from. PSSS: If you are an expert, you can write your opinion about the errors in this text in the comments. |

The bumblebee is a large and abundantly pubescent bee. It is quite difficult to confuse it with any other insect. He is a large number of species that are not common in the tropics, like all other insects, but vice versa, in temperate latitudes.

Habitat

The genus of bumblebees includes more than 300 species that live mainly in the temperate latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere, but many also go beyond the Arctic Circle and live in the tundra of Novaya Zemlya, Greenland and other islands of the Arctic, including those located less than 900 km from the pole itself. These bees are the northernmost. Many live at the bottom of the glaciers. In the tropics, bumblebees are practically not found, you can only find a couple of species in the Amazon. Several species also live in tropical Asia, but in southern Africa they do not exist at all.

Lots of bumblebees in South America. In the Australian regions, these insects have never been, they were brought there by man for pollination of red clover.

Bumblebee species

In Europe, there are about 53 species. The types of bumblebees differ in their size and color, but despite this, it will be difficult for an inexperienced person to distinguish a specific species. Some of the most common are:

Earth bumblebee;

garden bumblebee;

meadow bumblebee;

Arable bumblebee;

Stone bumblebee;

City bumblebee.

It is most problematic to distinguish between types of earthen bumblebees, as there are dark, light, great and romcrypts. And by the way, all these species are very similar to the stone bumblebee.

Flight of the Bumblebee

There is an opinion that the bumblebee supposedly cannot fly, as this contradicts the science of aerodynamics, but still, somehow it does it. Bumblebee wings create temporary powerful forces that appear at the beginning and end of each stroke. These forces are not explained by braking. They reach a maximum with each stroke and the insect's wing begins to rotate. This suggests that it is this rotation that plays an important role in the flight of the insect.

bumblebee nest

In the spring, in mid-April, you can often see large bumblebees that fly low above the ground. From time to time they land and burrow under foliage or in burrows dug in the ground. These are females that survived the winter, they want to find a place to breed. The nest of a bumblebee is a small ball of moss, grass, straws, twigs, etc. Basically, females build a nest in someone's abandoned burrows, rooftops or birdhouses.

(genus Bombus Latr. of the Apidae family of the Hymenoptera order) are found almost throughout our country, even in the Far North. In total, about 100 of their species are known in the USSR (Skorikov, 1922). These are typically social insects, but they differ from honey bees, ants and termites in that the bumblebee family exists in nature for only one season. The females, fertilized in autumn, remain wintering, having scattered from the nest and buried shallowly in the turf in glades, forest edges, and slopes. With the onset of spring warmth, the females leave their winter shelters, and in April - May they can already be seen on flowering willows: without top dressing on early flowering honey plants, eggs will not ripen. Bumblebees can also be seen on other early flowering plants - river gravel, hazel, fruit trees. Having restored their strength due to the nectar collected on the flowers, the females begin to look for nesting sites. The movements of such “searching” females are characteristic: they slowly fly low above the ground, often sit down, carefully examining holes and crevices in the ground, on trees, and building cladding. They are attracted by all sorts of black spots and objects resembling the entrance to a mink. Often at this time, females fly into buildings. They select nest rooms that have some fibrous insulation material, such as past-year rodent burrows, where you can use the nesting litter left by the animals after raising their cubs. Very many species of bumblebees are ecologically associated with rodents, and a decrease in the number of rodent burrows in any locality leads to a decrease in the number of bumblebees.

Other bumblebees (they are also a whole group of species) settle on the ground - in damp meadows, fields, in the forest. They build hummock-shaped nests from dry moss or finely crumbled past-year-old foliage; A "cap" of plant residues also serves as thermal insulation. Some types of bumblebees settle both on the ground and underground. Having arranged an insulated nest with a diameter of 3-4 cm, the female delivers here on the "baskets" of her hind legs (like a honey bee) a significant amount of pollen from spring honey plants (late-nesting species - clover pollen), folding it into a compact -ny lump ("briquette" of pollen) at the bottom of the nesting cavity. At the exit, the female builds a voluminous wax vessel - a honey "pot" filled with liquid honey during foraging flights. The female lays several eggs on the "briquette" of pollen and covers them with a wax vault on top, and she sits on top of it and, clinging tightly, heats the eggs.

The temperature inside the bumblebee nest is maintained at the expense of "burning" the nectar by insects at a level of 29–30°C (Eskov, 1982). Soon, larvae emerge from the eggs, and the female immediately starts feeding them, opening the wax wall of the larval package for a while and sticking her proboscis into the hole.

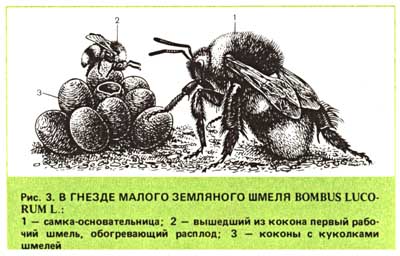

The larvae grow quickly. Having reached the maximum size, they weave silk cocoons for themselves, merged side by side with each other, inside which they turn into pupae. After some time, the first working bumblebees emerge from the co-cons. They are very small in size, but nevertheless they not only perform internal work in the nest (Fig. 3), but also fly in the field for a bribe. In many species of bumblebees, small workers of the first generation can already be seen on red clover flowers. The first flight of a bumblebee from the nest - the so-called orientation flight, or flight in the language of beekeepers - has characteristic features: the insect, turning its head towards the notch, flies in the form of ever-expanding arcs. So the bumblebee remembers appearance notch, near and far landmarks. The next batch of eggs is placed by the female on the top or side of unopened cocoons. As new working bumblebees emerge from them, the uterus flies out into the field less and less and is mainly engaged in laying eggs and heating them; the brood is also heated by working bumblebees. Their second generation differs from the first in larger sizes. Working bumblebees of the latest generations, released at the end of summer, are only slightly inferior in size to females. In general, workers in bumblebees, honey bees, and ants are underdeveloped females.

The nest (bumblebee "cone") also grows due to the construction of new cocoons, some of which, after bumblebees emerge from them, are converted by working bumblebees into honey "pots". A large bumblebee "cone" can reach quite large sizes (up to 20 cm in diameter or more). Most of the bumblebee families encountered now in nature have 30-100 individuals by the end of summer. Worker bumblebees daily prepare for feeding the larvae, in addition to honey, a large amount of pollen stored in the nest in special "pockets" on the side of the cocoons in the form of a slightly moistened and compacted mass - perga. Foraging flights take place during almost the entire daylight hours (and sometimes even on bright nights), noticeably increasing in the late morning and especially in the evening (morning and evening "peaks" of flight activity). In many species of bumblebees, during the season, a change of females takes place: a stranger, not laying a nest, penetrates into the nest, and kills the decrepit ancestor. The change of females is a natural phenomenon that has a positive effect on the size of the family. Such shifts take place up to six times a season, and females often belong to different types. Morphologically, ancestral females and successor females do not differ from each other. Females making “search” flights in the middle and late summer are mostly continuers looking for a family. desired type bumblebees in the corresponding phase of its development.

Bumblebees of long-proboscis species (garden, field, stone, comber bumblebee and some others) are especially attached to clover, which collect nectar and pollen from clover heads with great dexterity and speed. Bumblebees with a relatively short trunk (for example, a small earthen one) often get nectar in an "illegal" way, biting through the flower tube at the nectar and sticking their proboscis into the hole. Subsequently, honey bees also willingly use these bites. It was believed that such “operator” bumblebees harm seed production, without producing pollination: when extracting nectar, they do not touch the anthers and stigmas. Recent studies refute the harmfulness of the "operators" (Bilinski, 1970): in this way they get only nectar, while they get the pollen necessary for feeding the larvae from clover flowers in accordance with all the rules, through the corolla, participating in normal cross-pollination of clover; long-proboscis bumblebees never use the pro-kuses of "operators".

Bumblebees of long-proboscis species (garden, field, stone, comber bumblebee and some others) are especially attached to clover, which collect nectar and pollen from clover heads with great dexterity and speed. Bumblebees with a relatively short trunk (for example, a small earthen one) often get nectar in an "illegal" way, biting through the flower tube at the nectar and sticking their proboscis into the hole. Subsequently, honey bees also willingly use these bites. It was believed that such “operator” bumblebees harm seed production, without producing pollination: when extracting nectar, they do not touch the anthers and stigmas. Recent studies refute the harmfulness of the "operators" (Bilinski, 1970): in this way they get only nectar, while they get the pollen necessary for feeding the larvae from clover flowers in accordance with all the rules, through the corolla, participating in normal cross-pollination of clover; long-proboscis bumblebees never use the pro-kuses of "operators".

With an abundance of honey and pollen flora near the nest, bumblebees take bribes right there, without flying far. A bumblebee family of medium power, located, say, in the midst of a profusely flowering clover field, most intensively processes a plot within a radius of 40-50 m, i.e., an area of 0.05-0.07 hectares. Bumblebees are very accommodating and excellently get used to the close proximity of a person. They are incomparably more peaceful than honey bees, especially those families near which people often visit without harming them. When opening a hive with bumblebees, in which a family regularly “guarded” by a person lives, you can work without a beekeeping mask, without fear of bites. Some families are somewhat more aggressive, taken in nature in an already developed form and previously subjected to disturbance there, and then transferred to another place in order to pollinate clover. But they can sting only when opening the nest. A bumblebee, working on a flower, does not sting, even if it is driven away (but, of course, without grabbing it with your fingers).

The peace-loving and accommodating of bumblebees, good visual memory, excellent adaptability, well-known "smartness" make it very easy to work with them.